Previous: “Governance and Administration in Gerasa“

Note: This article synthesizes archaeological and historical evidence spanning from approximately 1 AD to 200 AD to present a comprehensive picture of Gerasa’s social structure during the early Roman imperial period.

Walking through the bustling streets of ancient Gerasa, a visitor would encounter a remarkable tapestry of peoples, languages, and social classes. Far from a homogeneous society, Gerasa represented a complex social ecosystem where Greek-speaking elites, Roman officials, local merchants, craftspeople, and laborers all interacted within the framework of imperial Roman rule. Understanding this social landscape provides crucial context for appreciating how Gerasenes lived, worked, and worshipped during the city’s golden age.

The Elite: Civic Notables and Priestly Families

At the apex of Gerasene society stood a relatively small group of wealthy and influential families who dominated civic affairs and religious life. Epigraphic evidence reveals that these elites often held multiple civic positions, served as priests, and acted as benefactors who financed major public works.

Inscriptions discovered throughout Gerasa, particularly in the Sanctuary of Zeus, provide glimpses into this upper echelon. Notable among these is a Greek inscription from the early 1st century AD that records the donation of 10,000 drachmas (~$2.5 millions) by a certain Titus Pomponius of the tribe Scaptia and his wife Manneia Tertulla for the construction of buildings in the sanctuary. This substantial sum far exceeded the typical donations of 1,500 drachmas (~$370,000) made by local gymnasiarchs, highlighting the vast wealth gap between the highest elites and other notable citizens.

The elite class was comprised primarily of Hellenized families who, despite their adoption of Greek culture and language, often had local Semitic origins. Names documented in inscriptions frequently combine Greek and Semitic elements, suggesting a blended cultural identity. Family connections were paramount, with several generations serving in prominent positions. For example, an inscription from 9/10 AD mentions Démétrios, son of Apollônios and grandson of Daisôn, identified as “former priest of Augustus,” while another from later in the century refers to Sarapiôn, son of Apollônios and grandson of Démétrios, who served as priest of Nero.

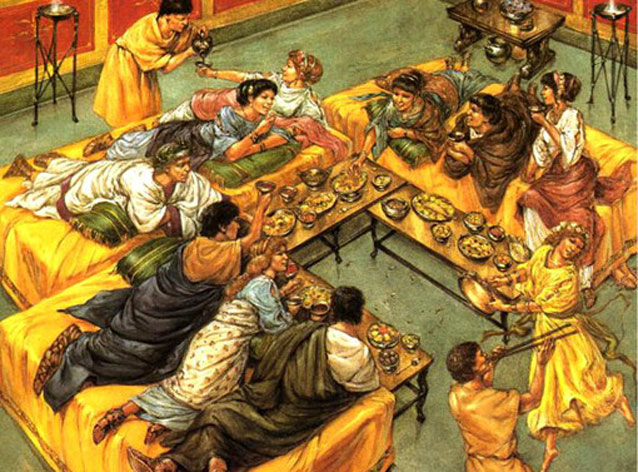

The elite jealously guarded their status through strategic marriages and by monopolizing key religious and civic offices. Their residences, mostly unexcavated but surely grand by local standards, would have occupied prime locations in the city, featuring peristyle courtyards, decorated reception rooms, and private bathing facilities.

-> Learn more about Gerasa’s religious landscape in my “Religious Landscape of Gerasa” article.

Roman Presence: Officials, Veterans, and Merchants

The Roman presence in Gerasa formed a distinct social group. While relatively small in number, their influence was substantial. Three main categories of Romans can be identified:

First were the imperial officials and administrators. After Gerasa was incorporated into the newly created province of Arabia in 106 AD, the city became the seat of the provincial procurator – the official responsible for financial administration – even though the provincial capital was at Bostra. Inscriptions document numerous procurators and their staff, including freedmen who served as clerks, record-keepers, and messengers in the procuratorial office.

Second were military veterans, who after completing their service often settled in provincial cities like Gerasa. Epigraphic evidence shows these veterans frequently rose to become influential members of local society. Several inscriptions mention individuals bearing Roman names who are identified as “former centurions” and who subsequently held civic positions. One inscription refers to a certain Flavius Munatius, a local councilor (bouleute) and former priest, who was also the son of a centurion and had attained equestrian rank. These veterans and their descendants formed an important bridge between Roman and local interests.

Third were Roman merchants and businesspeople drawn to Gerasa’s commercial opportunities. Although less visible in the epigraphic record, their presence is attested indirectly through imported goods found in archaeological contexts.

The Roman presence introduced new architectural forms, religious practices, and social customs to Gerasa, contributing to its increasingly cosmopolitan character during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

-> Discover more about Roman architectural influences in my “Walking Through Ancient Gerasa: A Monument-by-Monument Guide“ article.

The Middle Classes: Merchants, Craftspeople, and Freedmen

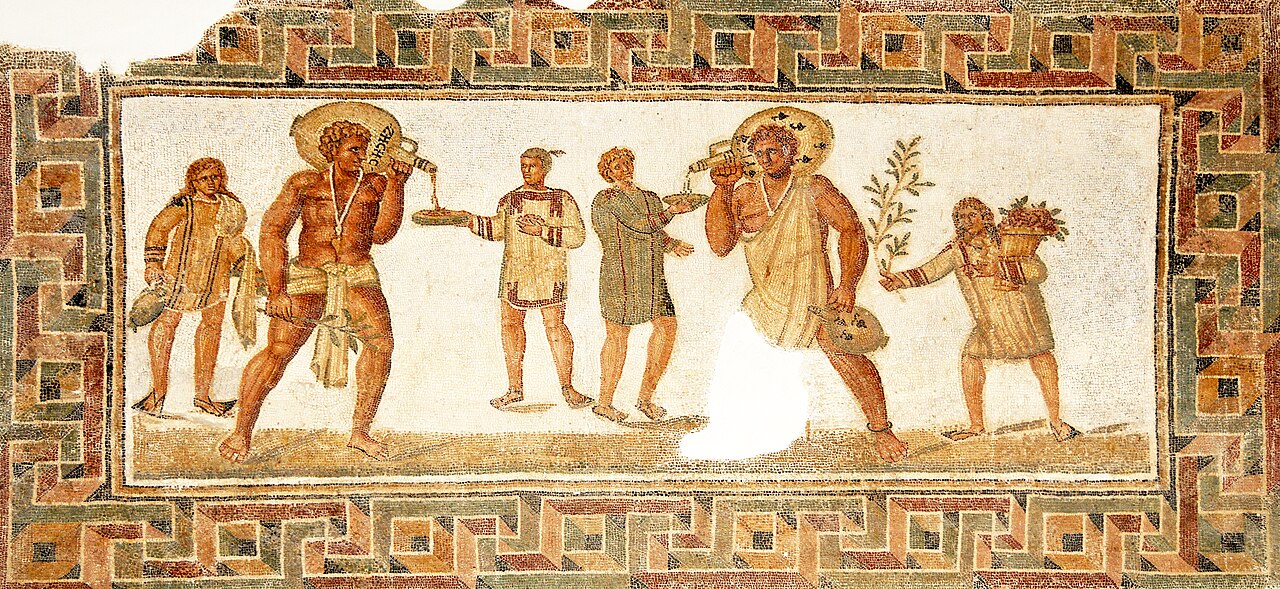

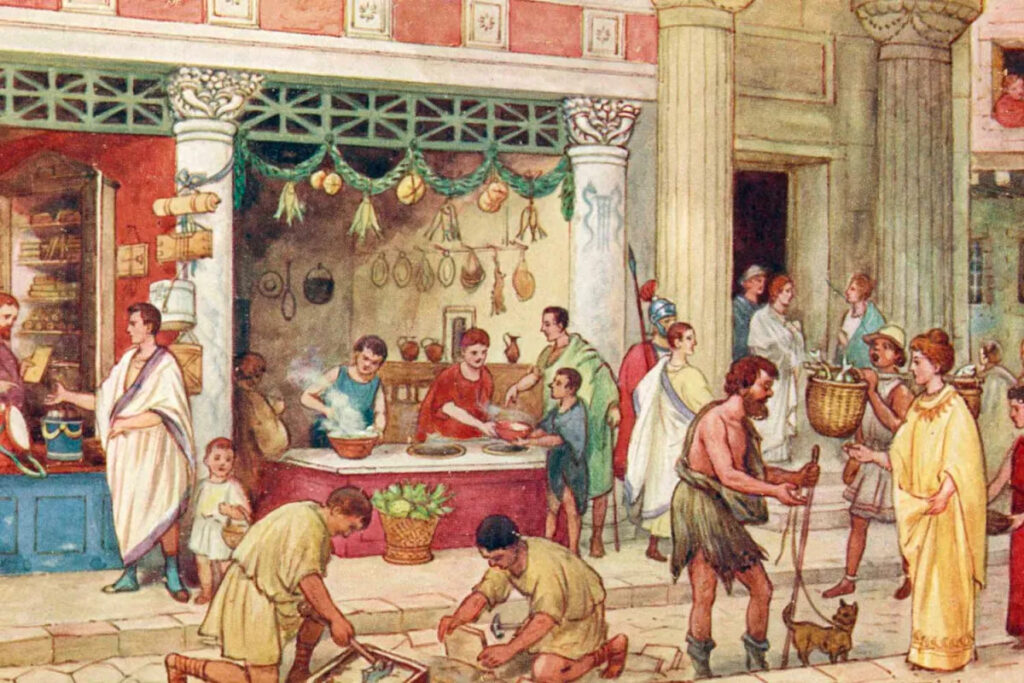

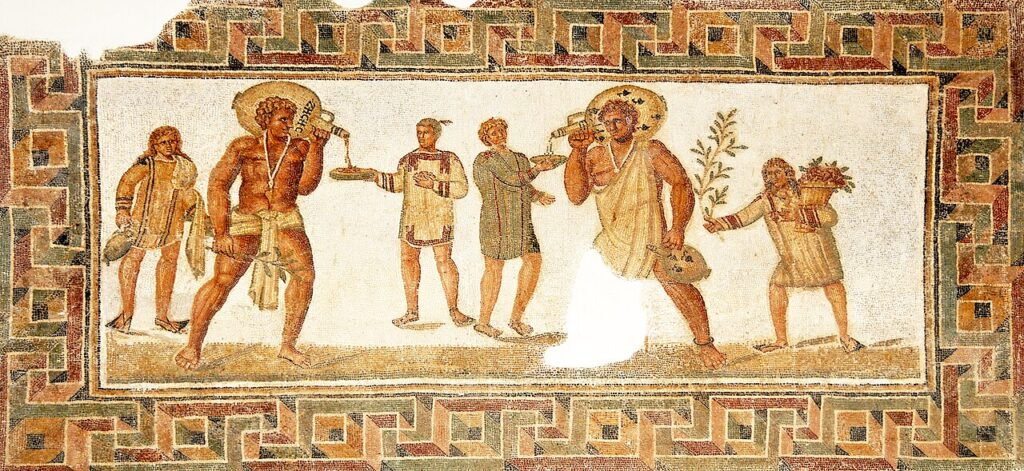

Between the elite and the laboring poor existed a substantial middle stratum of Gerasene society. This diverse group included merchants, shopkeepers, skilled craftspeople, and successful freedmen.

Archaeological evidence for this middle class comes primarily from small workshops and commercial spaces that lined Gerasa’s colonnaded streets. These typically included a front shop area opening onto the street with living quarters in the back or on an upper floor. The owners of these establishments formed the backbone of the urban economy.

Craftsmanship flourished in Gerasa, with archaeological evidence showing active production of pottery, metalwork, glassware, and textiles. The so-called “Jerash bowls,” distinctive fine pottery with impressed decorations, represent the high quality of local ceramic production during the Roman period. Workshops for stone carving and sculpture production have also been identified, indicating a substantial market for luxury decorative items.

Inscriptions occasionally mention professional associations or guilds. One notable example refers to the “gardeners of the upper valley” of the Chrysorrhoas, who formed an association that participated in the civic and religious life of the city. Such organizations provided both economic coordination and social solidarity for their members.

Freedmen (ex-slaves) occupied a complex position in this middle stratum. While some, particularly those formerly owned by wealthy Romans or members of the imperial household, could achieve considerable wealth and status, they remained socially distinct from freeborn citizens. Several inscriptions document imperial freedmen serving in the procurator’s office, some of whom erected monuments or made donations, suggesting they had attained significant means.

The Lower Classes: Laborers, Slaves, and the Rural Poor

The lower classes, though forming the numerical majority of Gerasa’s population, are the most poorly documented in both archaeological and epigraphic records. They lived primarily in the city’s less developed quarters, in modest multi-room dwellings built of local limestone, or in the surrounding countryside.

Urban laborers worked as porters, construction workers, domestic servants, and in other unskilled or semi-skilled capacities. Archaeological evidence for their living conditions is limited, though excavations in the Northwest Quarter of Jerash (Gerasa) have revealed modest domestic structures that may represent their dwellings. These simpler homes lacked the decorative elements and spacious layouts found in elite residences.

Slavery was an established institution in Gerasa, as throughout the Roman world. Slaves served in various capacities: as domestic servants in wealthy households, as laborers in workshops and on rural estates, and as assistants in the public baths and other municipal facilities. Manumission (the freeing of slaves) was practiced, with several inscriptions recording freed slaves, some of whom achieved positions in the imperial administration.

The rural poor, living in villages and farms in Gerasa’s territory (chora), formed an essential part of the economic landscape. They cultivated the fertile lands along the Chrysorrhoas valley, producing grain, olives, grapes, and other crops that fed the urban population. Evidence of agricultural installations, including olive oil presses, has been found throughout the region, testifying to the intensive cultivation of the countryside. While these farmers had limited political influence, their economic importance was recognized, as shown by the organization of the “gardeners of the upper valley” mentioned earlier.

-> Explore more about Gerasa’s agricultural landscape in our “The Decapolis: Ten Semi-Autonomous Cities in Rome’s Shadow “article.

Ethnic Composition and Cultural Identity

Gerasa’s population reflected the city’s position at the crossroads of different cultural worlds. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence reveals several distinct ethnic components that contributed to the city’s cultural makeup.

The Greek-speaking population formed the core of the civic elite. While many were descendents of Hellenized local families rather than ethnic Greeks, they embraced Greek culture, language, and civic institutions. Their cultural dominance is attested by the overwhelmingly Greek character of public inscriptions. Even during the Roman period, Greek remained the primary language of administration and high culture in Gerasa. The cultural aspirations of this group are evident in the city’s architecture, such as the temples, theatres, and other public buildings built in Greco-Roman style.

The indigenous Semitic population, though often Hellenized to varying degrees, maintained aspects of their pre-Greek cultural identity. Personal names preserved in inscriptions provide the clearest evidence for this population. While Greek names predominate, especially among the elite, Semitic names such as Malchiôn, Zébinas, and Zébédos appear occasionally, suggesting the persistence of local onomastic traditions. The architect of the Sanctuary of Zeus, identified in an inscription as “Diodôros, son of Zébédos, of Gérasa,” exemplifies this cultural blending – a man with a Greek personal name but whose father bore a Semitic name.

Evidence for a Jewish community in Gerasa comes from various sources. Josephus mentions that during the First Jewish Revolt (66-70 AD), the inhabitants of Gerasa spared their Jewish citizens, indicating a significant Jewish presence in the city. Archaeological confirmation comes from the discovery of a fragment of a Jewish “purity vessel” in the Northwest Quarter, of a type associated with ritual purification practices and likely dating to before 70 AD. This Jewish community would have maintained its distinct religious practices while participating in the broader economic and social life of the city.

Romans and other western immigrants, though numerically small, brought significant cultural influences. As noted earlier, these included officials, veterans, and merchants. Their presence is marked by Latin inscriptions, which comprise about one-seventh of the epigraphic finds from Gerasa, and by the introduction of distinctly Roman architectural features such as bath complexes.

Family Structure and Gender Roles

Gerasene family structure generally followed patterns common throughout the eastern Mediterranean during the Roman period. The family unit typically consisted of a nuclear family – parents and children – though extended family connections remained important, especially among the elite.

Marriage was the foundation of family life, with marriages arranged to strengthen social ties and secure property. Among the upper classes, marriage alliances were crucial strategies for maintaining status and wealth. Women normally married in their teens, while men married somewhat later. The city’s Greek heritage meant that women had limited public roles, though they could own property and conduct certain kinds of business.

The epigraphic record provides glimpses of women’s status in Gerasene society. Several inscriptions mention women as donors or dedicants, usually in conjunction with their husbands. For example, the previously mentioned inscription records Manneia Tertulla making a substantial donation alongside her husband Titus Pomponius. Women also appeared as priestesses in certain cults, particularly those dedicated to female deities like Artemis.

Children were highly valued, as in most ancient societies, with sons particularly prized as heirs and continuers of the family line. Elite families invested significantly in their sons’ education, which would have included Greek literature, rhetoric, and philosophy – skills necessary for participation in civic life. Evidence for formal educational institutions in Gerasa is limited, though the city certainly would have had teachers and perhaps schools similar to those known from other cities in the eastern provinces.

Family tombs, located in necropolis areas outside the city walls, reflect the enduring importance of family connections even in death. While relatively few funerary inscriptions have been discovered at Gerasa compared to other types of texts, those that exist often emphasize family relationships and lineages.

Social Mobility and Status Markers

Despite the hierarchical nature of Gerasene society, some degree of social mobility was possible. The clearest path to advancement was through military service. Several inscriptions document cases where military veterans, particularly centurions, or their descendants achieved positions of prominence in local society, sometimes even attaining equestrian rank.

Commercial success offered another avenue for advancement. Successful merchants and craftspeople could accumulate wealth that allowed their descendants to pursue more prestigious careers and eventually join the civic elite. The most successful freedmen might also achieve considerable wealth, though social prejudices limited their full acceptance into elite circles.

Roman citizenship served as an important status marker in Gerasa. Prior to the Constitutio Antoniniana of 212 AD (which granted citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire), Roman citizenship was relatively restricted. Epigraphic evidence from Gerasa shows that before this universal grant, citizens were predominantly either Romans who had settled in the city or locals who had acquired citizenship through military service or imperial favor.

The epigraphic record reveals that the gentilice Flavius was particularly common among Gerasene citizens before the wide spread of the Aurelii in the 3rd century. This suggests that many families received citizenship during the Flavian dynasty (69-96 AD), possibly in recognition of the city’s loyalty to Rome during the First Jewish Revolt. The military career appears to have been a privileged means of accessing Roman citizenship in Gerasa, including among notable families.

Conclusion

The social landscape of Gerasa between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD reflected both the city’s local cultural heritage and its integration into the wider Roman imperial system. The stratified society – with its elite families, Roman officials, middle-class merchants and craftspeople, and laboring poor – operated within a framework where Greek cultural forms predominated but where multiple ethnic and religious traditions coexisted.

Understanding this complex social ecosystem provides essential context for appreciating how the people of Gerasa navigated their daily lives, formed identities, and interacted across social boundaries during this pivotal period in the city’s history. Beyond the monumental architecture that dominates the archaeological remains, it was this diverse human community that gave Gerasa its distinctive character as one of the most prosperous cities of the Decapolis.

Sources: “Onomastique et Présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja “A New Inscribed Amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja “Un Exceptionnel Document d’Architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier et Jacques Seigne “Dédicaces de Statues ‘Portes-Flambeaux’ (Δαιδούχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot & Jacques Seigne “Water Management in Gerasa and Its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer “The Chora of Gerasa/Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger & Rubina Raja “New Perspectives on the City on the Gold River: The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project 2011–2017” by Achim Lichtenberger and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa/Jarash: Report on the Excavation Campaign 2017” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah – Sonia Mucznik “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas, Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja “Jarash Hinterland Survey – 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker