Previous: “Social Classes and Demographics in Gerasa“

Note: While historical accounts span several centuries, this article presents a cohesive view of economic life in Gerasa during its peak development (1-200 AD), drawing from archaeological evidence and historical records.

The economic life of ancient Gerasa reflects its status as one of the most prosperous cities of the Decapolis, strategically positioned at the intersection of major trade routes. Archaeological evidence reveals a city that thrived on commerce, manufacturing, and agriculture, with a sophisticated economic infrastructure that supported its monumental architecture and cosmopolitan population.

A Center of Regional Trade

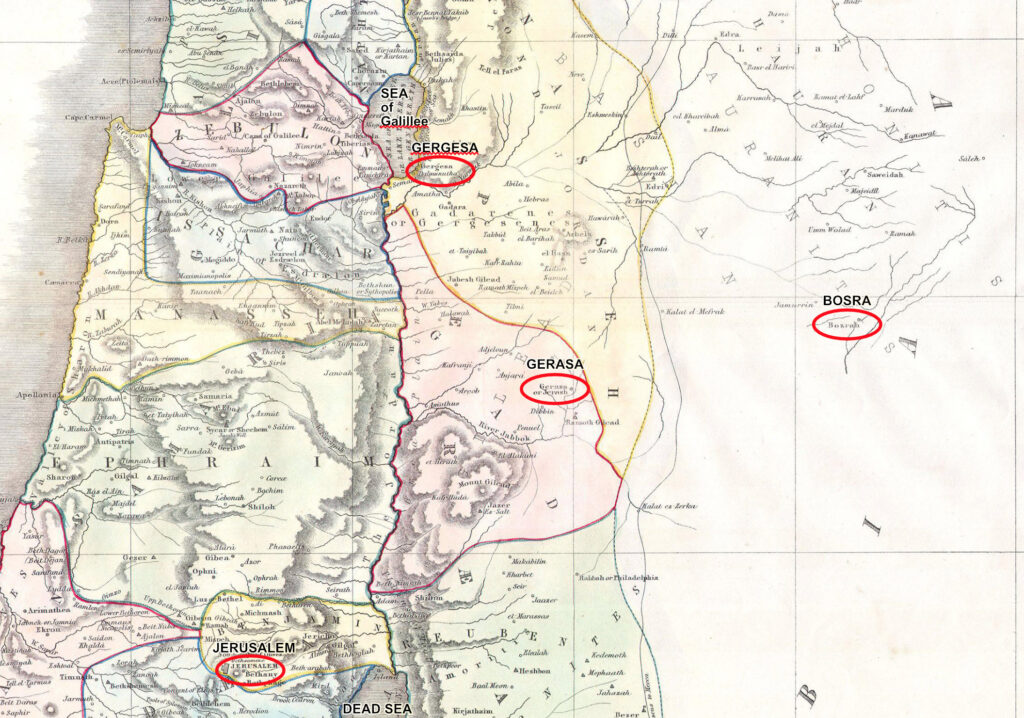

Gerasa’s economic success was largely attributable to its favorable geographic position. The city sat at a crucial intersection of north-south and east-west trade routes linking Syria with Arabia and the Mediterranean coast with territories to the east. This advantageous location made Gerasa a natural hub for merchants and traders coming from diverse regions.

The city’s economic importance was so significant that when the province of Arabia was formed in 106 AD, Gerasa was chosen as the seat of the provincial procurators while Bostra served as the capital. This administrative arrangement speaks to Gerasa’s commercial prominence, as procurators were primarily concerned with financial administration and tax collection.

The Chrysorrhoas River (aptly named the “Gold River”) was instrumental to Gerasa’s prosperity, providing water for agriculture and supporting various industries. The fertile land along its banks, particularly between Gerasa and Suf, was intensively cultivated, supporting what inscriptions refer to as “gardeners of the upper valley.” An inscription found in the North Theater references this organization of agriculturalists, suggesting they were more than simple gardeners – they were significant landowners who participated in the socio-political life of the city.

-> Learn more about how the Chrysorrhoas River shaped the city in my article “Physical Geography of Gerasa and Surroundings“

Industries and Manufacturing

Archaeological evidence reveals a diverse manufacturing sector that supported Gerasa’s economy and provided goods for both local consumption and export.

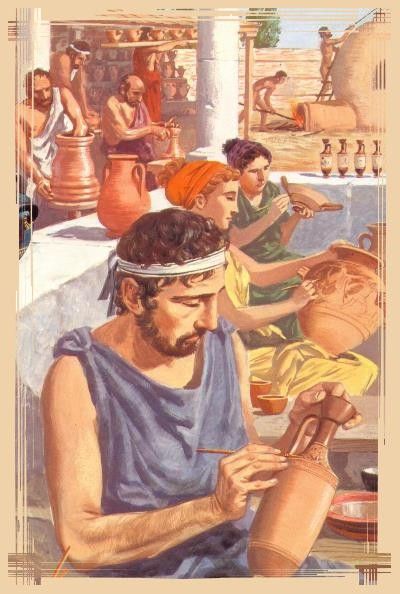

Pottery Production

The ceramic industry was particularly significant, with most pottery used in Gerasa being locally produced. Excavations have uncovered evidence of pottery workshops with various types and styles being manufactured, including the distinctive “Jerash Bowls” introduced in the later Roman period. These fine wares indicate the presence of skilled craftsmen and a market for luxury goods.

The capacity for large-scale pottery production suggests an export trade to surrounding regions, although the exact extent of this trade awaits further archaeological confirmation. The presence of some imported ceramic wares, though limited, indicates commercial connections with other Mediterranean regions.

Metallurgy and Stoneworking

Metallurgical activities were another important component of Gerasa’s economy. Excavations have revealed evidence of metal workshops within the city, where bronze and iron were worked into utilitarian objects, decorative items, and construction materials. An exceptional discovery was made in the sanctuary of Zeus, where evidence of a workshop for producing large bronze statues was found.

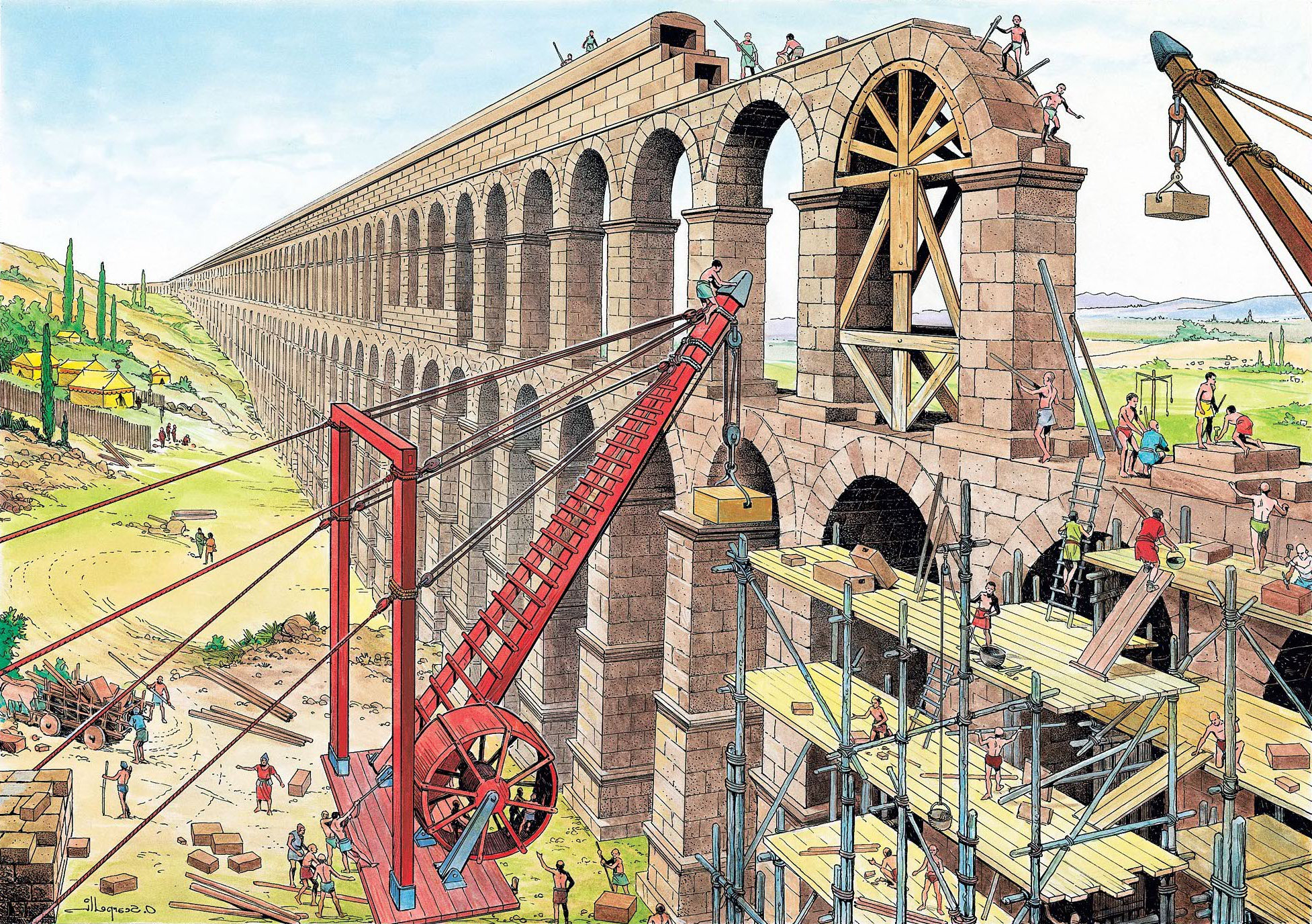

Stonecutting and masonry represented another major industry. The abundant local limestone served as the primary building material for the city’s impressive architecture. Quarries around Gerasa show evidence of extensive stone extraction activities, with different qualities of limestone being used for different purposes. The soft whitish limestone was used for general construction, while harder varieties were reserved for more important architectural elements.

The scale of public building projects in Gerasa would have required a substantial workforce of skilled and unskilled laborers, from architects and master masons to general construction workers. This construction economy was likely one of the city’s major employers during its periods of monumental building work.

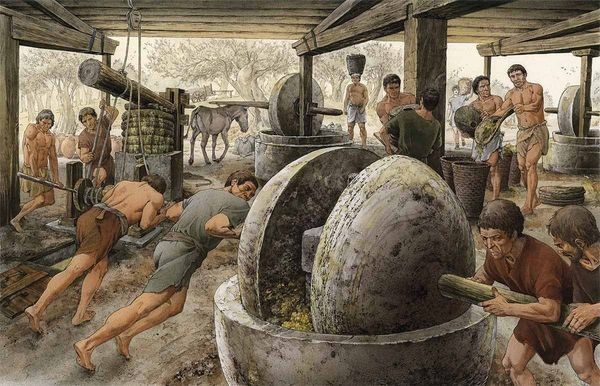

Olive Oil Production

Olive cultivation and oil production formed a cornerstone of Gerasa’s agricultural economy. Archaeological evidence of olive presses has been discovered in the immediate vicinity of the city and throughout its territory. One particularly notable find was a subterranean multi-chambered site containing the remains of an olive oil press, which had apparently been converted from a former tomb.

The production of olive oil would have not only provided a staple food and lamp fuel for local consumption but also an important export commodity. The durable nature of olive oil made it suitable for long-distance trade, and the reputation of Levantine olive oil was high throughout the Roman Empire.

-> Discover more about the physical structures that housed these industries in our article “Urban Layout of Gerasa (1-200 AD)“

Commerce and Market Life

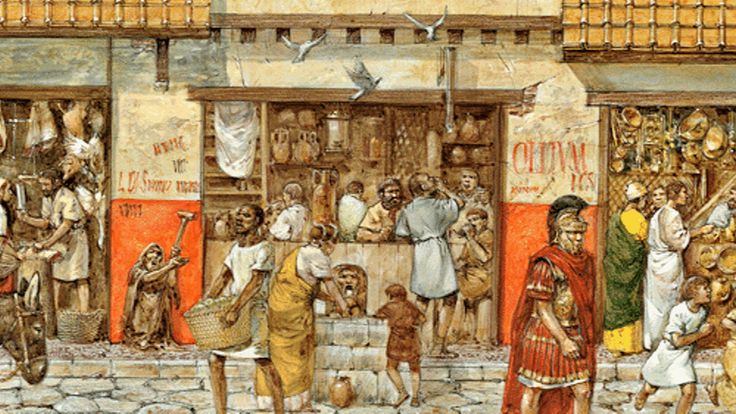

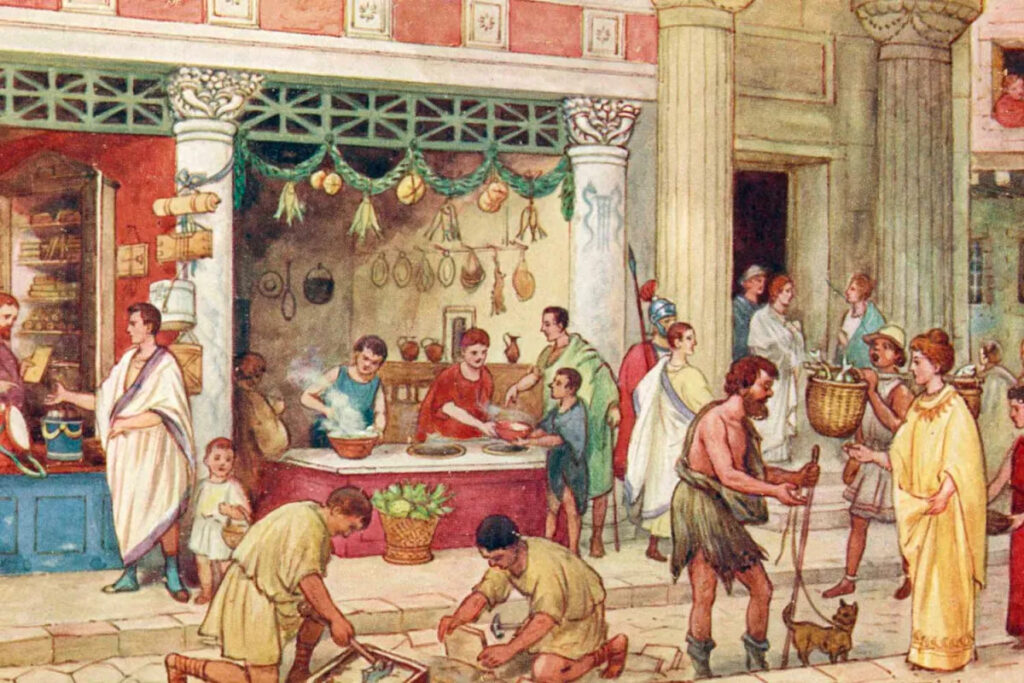

The commercial heart of Gerasa was concentrated along its colonnaded street and in specialized market areas. The imposing Nymphaeum, situated along the main street, was more than a decorative monument – it was a public gathering space where commercial activities would have taken place. Markets were typically situated near major intersections or gates where traffic would naturally concentrate.

Shops lined the main colonnaded street, housed in uniform structures behind the columns. These standardized commercial spaces, typical of Roman urban planning, would have displayed a wide variety of goods from everyday necessities to luxury items. The diversity of commodities available in Gerasa would have reflected its cosmopolitan nature and connections to wider trading networks. Different sectors of the city may have been dedicated to specific trades or products, following a pattern common in Roman provincial cities.

The macellum or marketplace would have been the center for daily commercial activity, where foodstuffs, household goods, and other commodities changed hands. The official responsible for overseeing market activities was the agoranome, a position attested to in inscriptions from Gerasa. These officials were tasked with ensuring fair trade practices, regulating weights and measures, and possibly overseeing public lighting – a key aspect of enabling commerce beyond daylight hours.

Currency and Financial Systems

The monetary system of Gerasa followed the standard Roman provincial pattern while maintaining some local distinctiveness. The city began minting its own bronze coins during the reign of Nero in 67/68 AD, coinciding with the First Jewish War. This timing suggests that the presence of military units in the region created a need for small change for local transactions.

The earliest coins from Gerasa featured depictions of Artemis, Zeus, or the city’s Tyche (personified fortune) on the reverse, while the obverse typically displayed the emperor’s portrait. These coins express civic pride and religious affiliations while acknowledging Roman authority. Particularly notable are coins showing Artemis identified with Tyche wearing a mural crown (corona muralis), emphasizing her role as the city’s protector.

For larger transactions, silver coins from other mints would have been used, particularly Tyrian silver, which played an important role in regional commerce and was accepted for the Temple Tax in Jerusalem before 70 AD. After the constitutio Antoniniana of 212 AD granted Roman citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire, there was a significant increase in persons bearing the name Marcus Aurelius in Gerasa, reflecting this major legal and economic change.

Banking activities and money-changing would have been essential services in a commercial center like Gerasa. Although direct evidence for banking facilities has not been discovered, the cosmopolitan nature of the city and its commercial importance suggest they must have existed, likely in the vicinity of the main market areas.

Trade Networks and External Relations

Gerasa’s prosperity depended on extensive trade networks connecting it to other urban centers in the region and beyond. The Decapolis cities formed a natural commercial network, with goods and people moving freely between them. Beyond this regional network, Gerasa maintained commercial connections with the Mediterranean coast, Arabia, and likely Parthian territories to the east.

The diversity of imported goods found in archaeological excavations tells us about Gerasa’s external trade connections. Marble architectural elements and statuary were imported from quarries in Asia Minor, Greece, and Egypt, indicating luxury trade with distant regions. Although most pottery was locally produced, some imported fine wares have been discovered, suggesting connections to production centers in other parts of the empire.

Epigraphic evidence reveals that prominent Gerasene citizens held positions of importance in other cities, including Rome itself, facilitating commercial and political networks beneficial to Gerasa’s economy. The cosmopolitan composition of the city, with its Greek, Roman, Arab, and Jewish elements, further enhanced its capacity to engage in far-reaching trade networks.

Conclusion

The economic life of Gerasa presents a picture of a prosperous provincial city deeply integrated into regional and empire-wide commercial networks. Its strategic location, fertile agricultural land, and diverse manufacturing sectors created a resilient economy that supported monumental construction projects and a sophisticated urban lifestyle.

Archaeological evidence continues to expand our understanding of Gerasa’s economic systems, revealing a city whose commercial vitality made it one of the most important urban centers in the region. This economic foundation was essential to Gerasa’s cultural achievements and its distinctive identity within the broader context of the Roman provincial world.

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja