Previous: “Social Classes and Demographics in Gerasa“

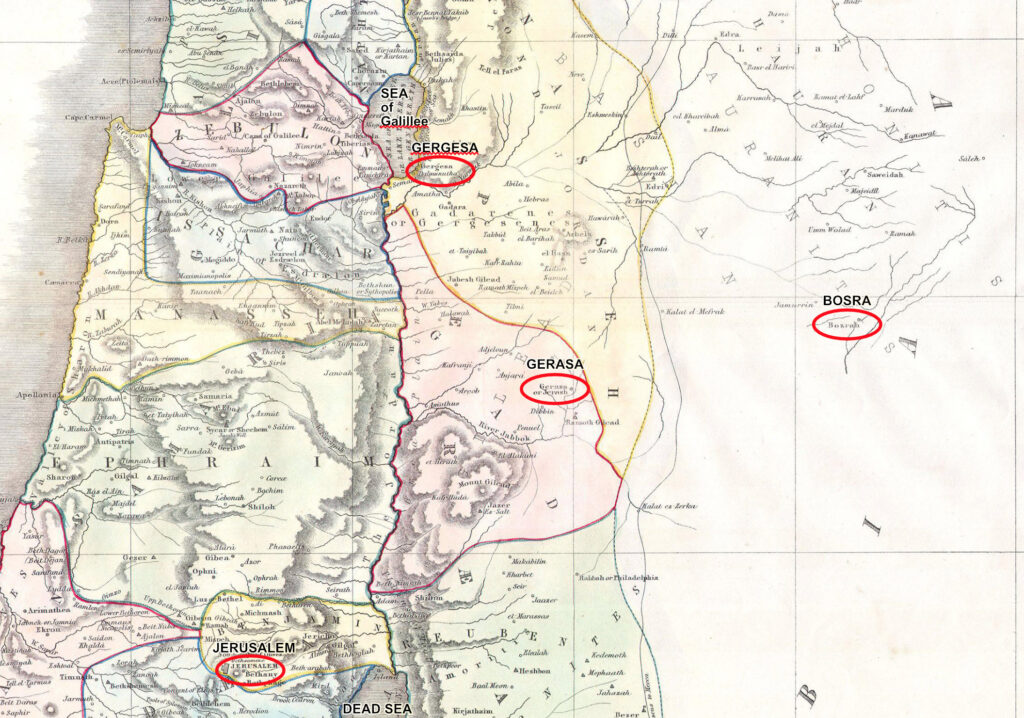

Note: This article combines historical evidence from approximately 1-200 AD to provide a comprehensive view of daily life in Gerasa during the early Roman Imperial period.

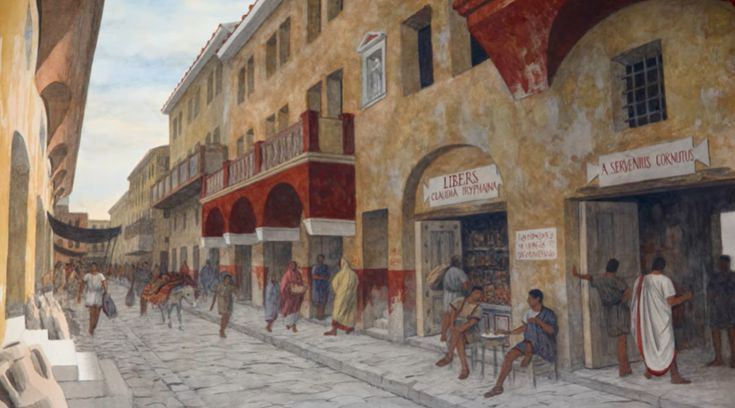

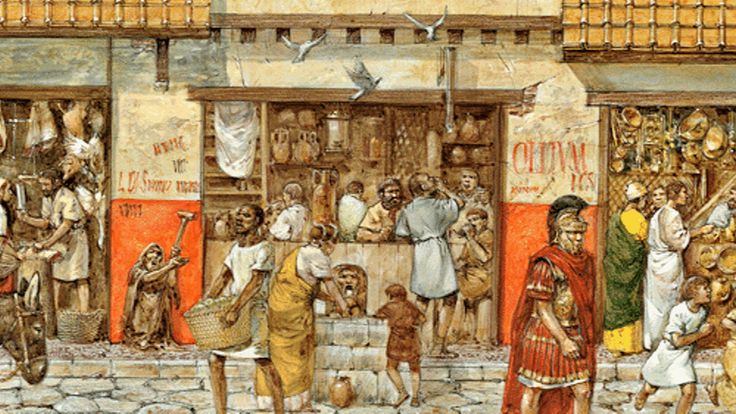

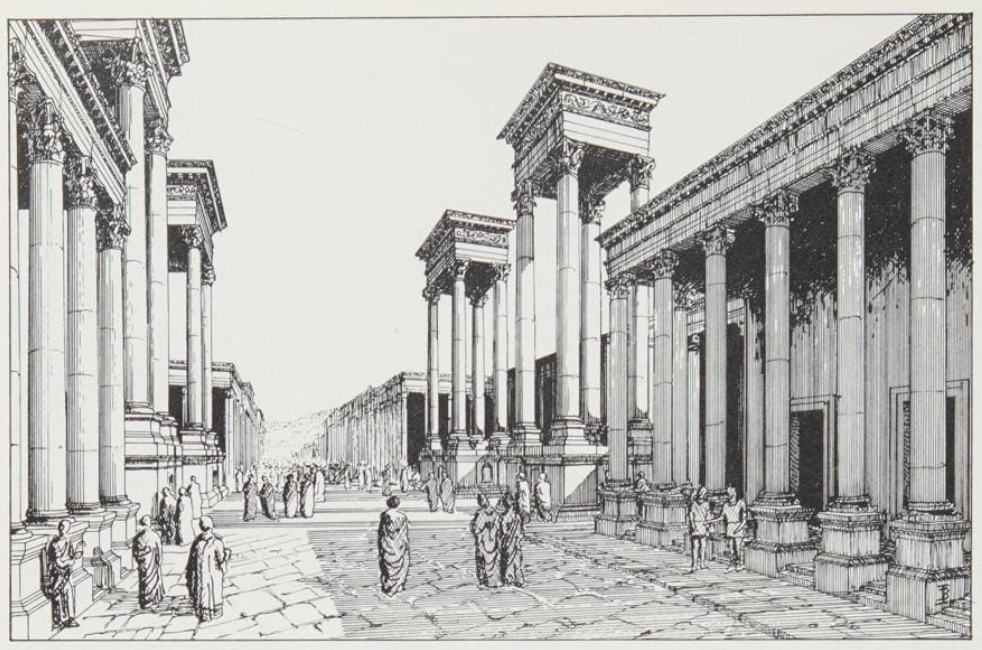

The streets of ancient Gerasa bustled with activity from dawn until dusk, filled with people going about their daily routines. From merchants setting up their stalls in the marketplace to priests preparing for rituals at the temples of Zeus and Artemis, the city pulsed with life. Drawing from archaeological evidence, inscriptions, and comparative studies of nearby Roman cities, we can reconstruct much about the daily experiences of Gerasenes during the first two centuries AD.

Food and Dining Customs

Daily Sustenance

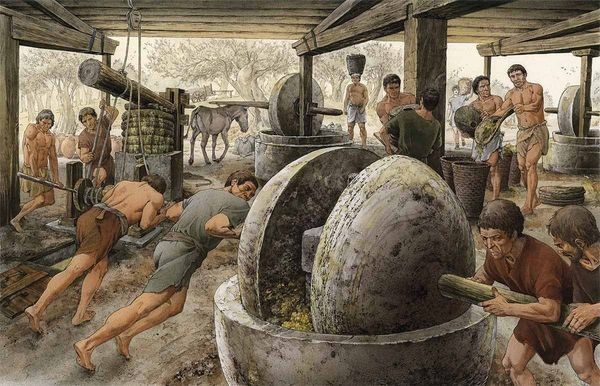

The diet of Gerasa’s inhabitants varied significantly depending on social status, but certain staples formed the foundation of most meals. Archaeological evidence from the site reveals that wheat, barley, olives, and various fruits were dietary mainstays. Olive cultivation was particularly important in the region, as evidenced by the primitive olive mills discovered in excavations.

For the average Gerasene, the day typically began with a simple breakfast (ientaculum) consisting of bread dipped in wine, perhaps accompanied by olives, cheese, or dried fruit. The midday meal (prandium) might include more bread, vegetables, cheese, and occasionally fish or meat for those who could afford it. The evening meal (cena) was the most substantial, especially for wealthier families who might enjoy several courses and entertain guests.

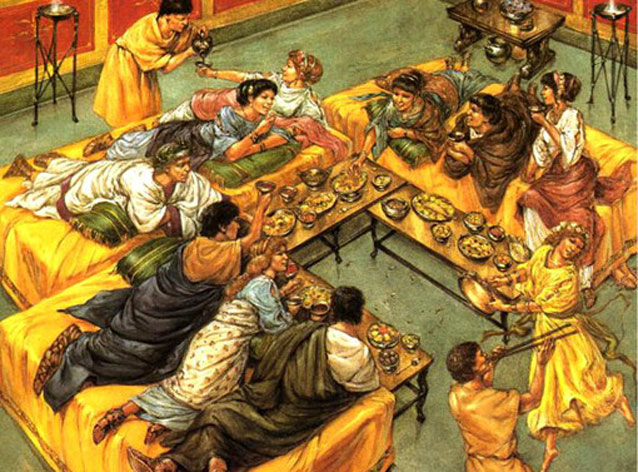

Dining Practices

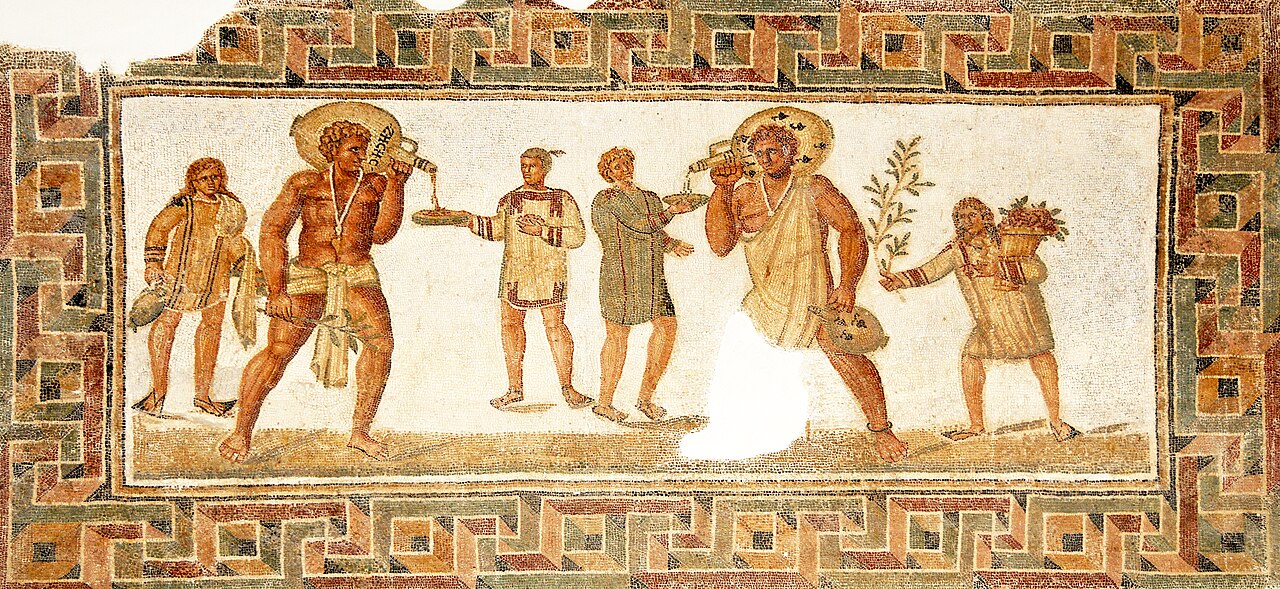

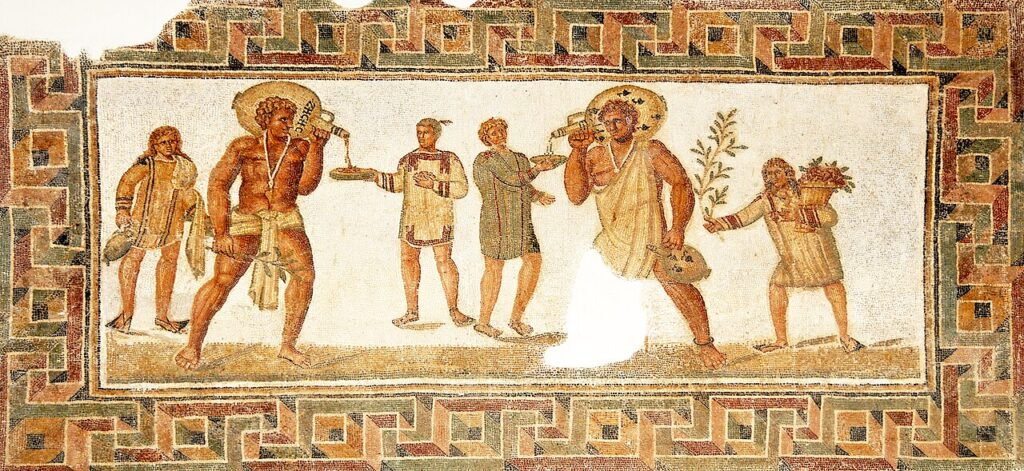

Wealthy households in Gerasa adopted Greco-Roman dining customs, reclining on couches (triclinia) around a central table while being served elaborate meals. These formal dining areas have been identified in some of the larger domestic structures excavated in the city. The “Dancing Satyr holding Dionysus’ babe” statue fragment discovered in Gerasa suggests the importance of Dionysian themes in elite dining contexts, where wine consumption was central to socializing.

For most inhabitants, however, dining was a simpler affair. Families gathered around low tables or simply sat together in the main room of their homes. Meals were typically eaten with the hands or with spoons, with bread often serving as both food and utensil to scoop up stews and sauces.

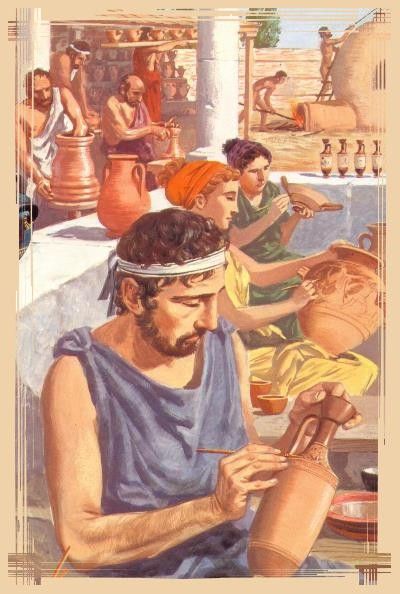

Water mixed with wine was the common beverage, with the quality of wine varying greatly. The presence of numerous ceramic vessels and amphorae found throughout excavations indicates widespread liquid storage and consumption. Local pottery production was significant to Gerasa’s economy, providing containers for food and drink.

-> Learn more about the economic foundations of Gerasa in our article “Economic Life in Gerasa”

Clothing and Personal Appearance

Everyday Attire

Clothing in Gerasa reflected both practical needs and cultural influences. The Mediterranean climate, with its hot summers and mild winters, dictated lightweight garments for much of the year, with additional layers during cooler months.

For men, the basic garment was the tunic (chiton in Greek or tunica in Latin), a simple rectangular cloth folded and sewn at the shoulders and sides, reaching to the knees or ankles depending on the style. Over this, free citizens might wear a toga for formal occasions, though this cumbersome garment was increasingly reserved for official functions. For everyday wear, a cloak (himation in Greek or pallium in Latin) was more practical.

Women typically wore floor-length tunics (stola), often belted at the waist, with a stole (palla) draped over the shoulders when in public. The quality of fabric and presence of decorative elements signaled social status. Archaeological finds, including small bronze pins and fibulae (brooches), attest to how these garments were fastened.

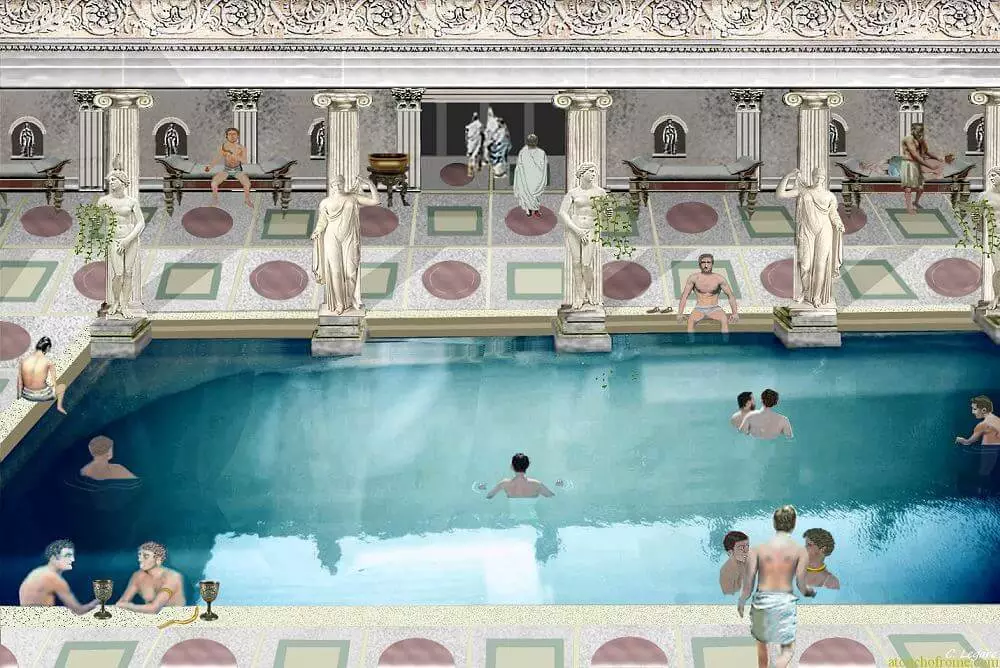

Personal Grooming

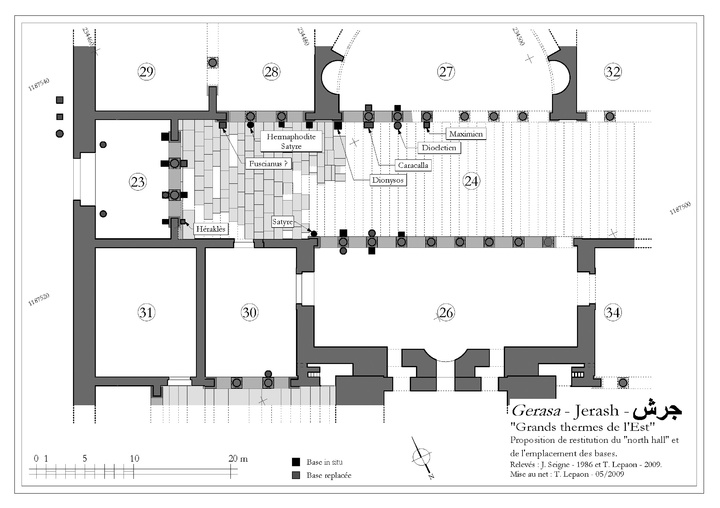

Personal appearance was important in Gerasa’s society. Inscriptions mentioning public baths indicate their significance for hygiene and socializing. The Great Eastern Baths complex, with its impressive scale, suggests that bathing was a major aspect of daily life for many Gerasenes.

Evidence from marble sculptural fragments discovered in Gerasa, including the “Aphrodite of Demetrius” and various portraits, provides insights into hairstyles and grooming ideals. Women’s hairstyles typically involved elaborate arrangements of curls and braids, often requiring the assistance of household slaves or family members. Men’s styles varied from short-cropped hair and clean-shaven faces in the early imperial period to longer hair and beards becoming more fashionable under Hadrian and the Antonines.

Cosmetics and perfumes were used by those who could afford them. The presence of small glass and ceramic containers in archaeological finds suggests the use of imported scented oils and locally produced alternatives.

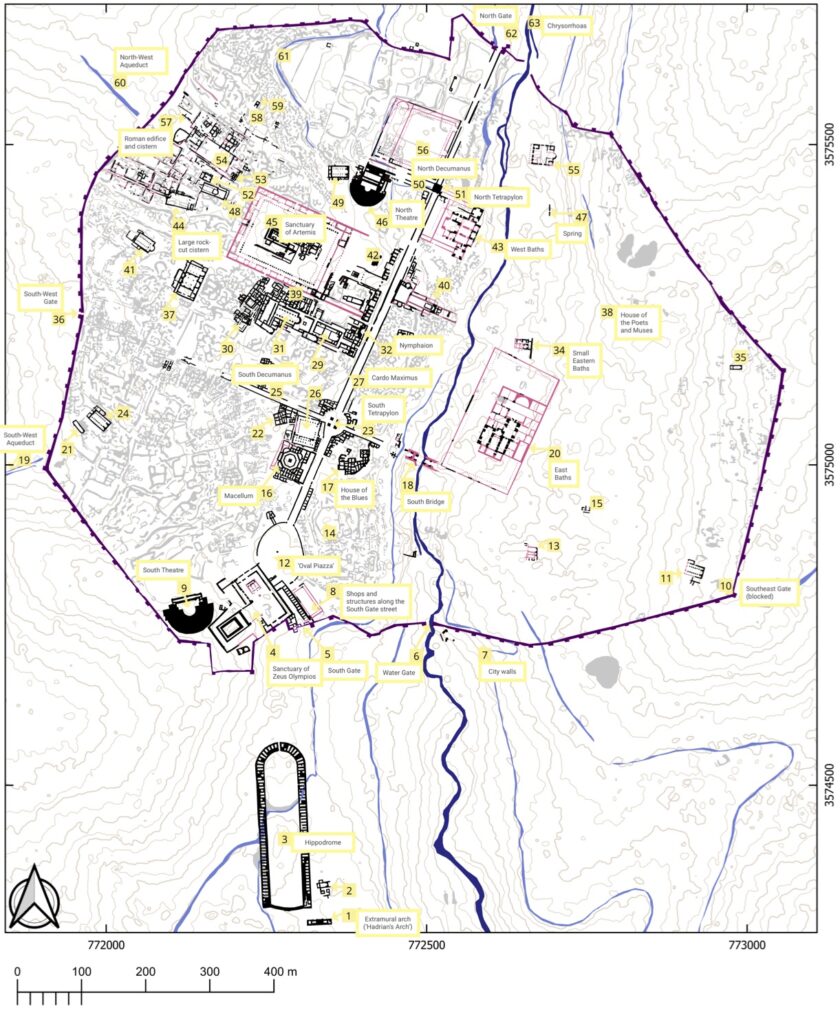

-> Discover the public buildings where Gerasenes socialized in our article “Walking Through Ancient Gerasa: A Monument-by-Monument Guide”

Work and Daily Occupations

Crafts and Trades

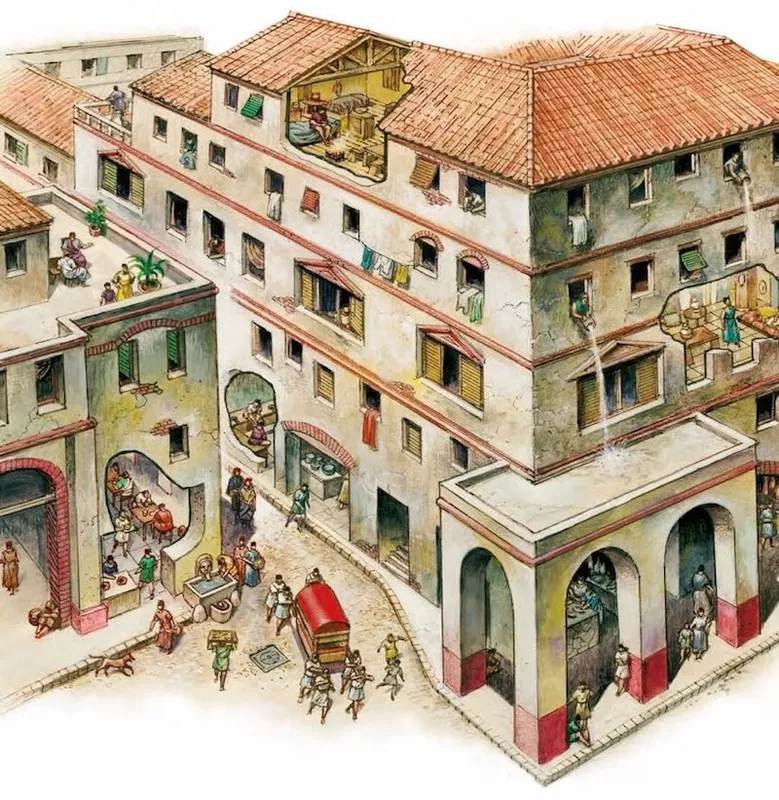

The workday in Gerasa typically began at dawn and continued until late afternoon. Artisans and craftspeople had workshops throughout the city, often with living quarters above or behind their workspace. Archaeological evidence points to a thriving craft economy, with specialized production in pottery, metalworking, stone carving, and textiles.

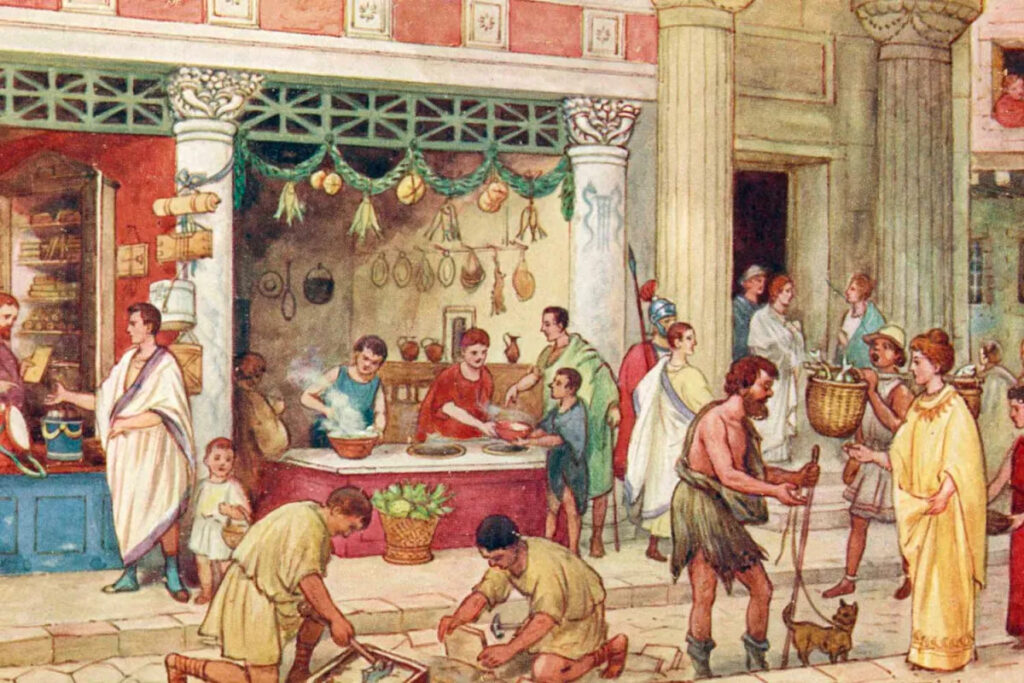

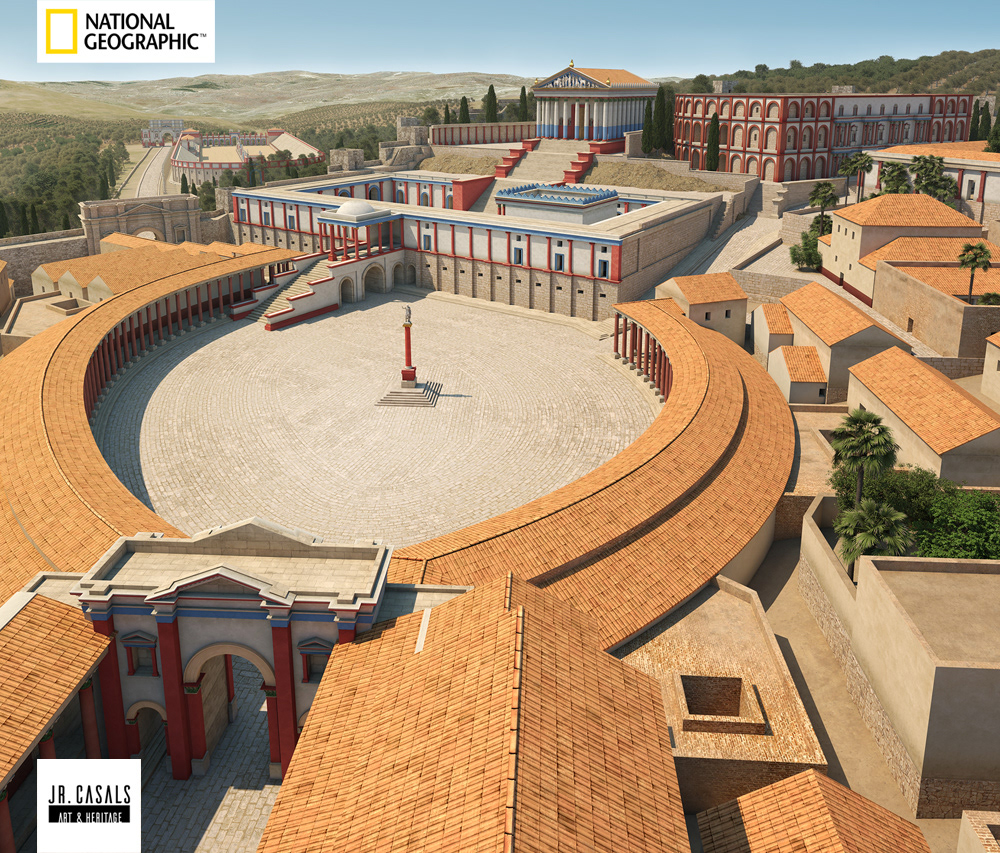

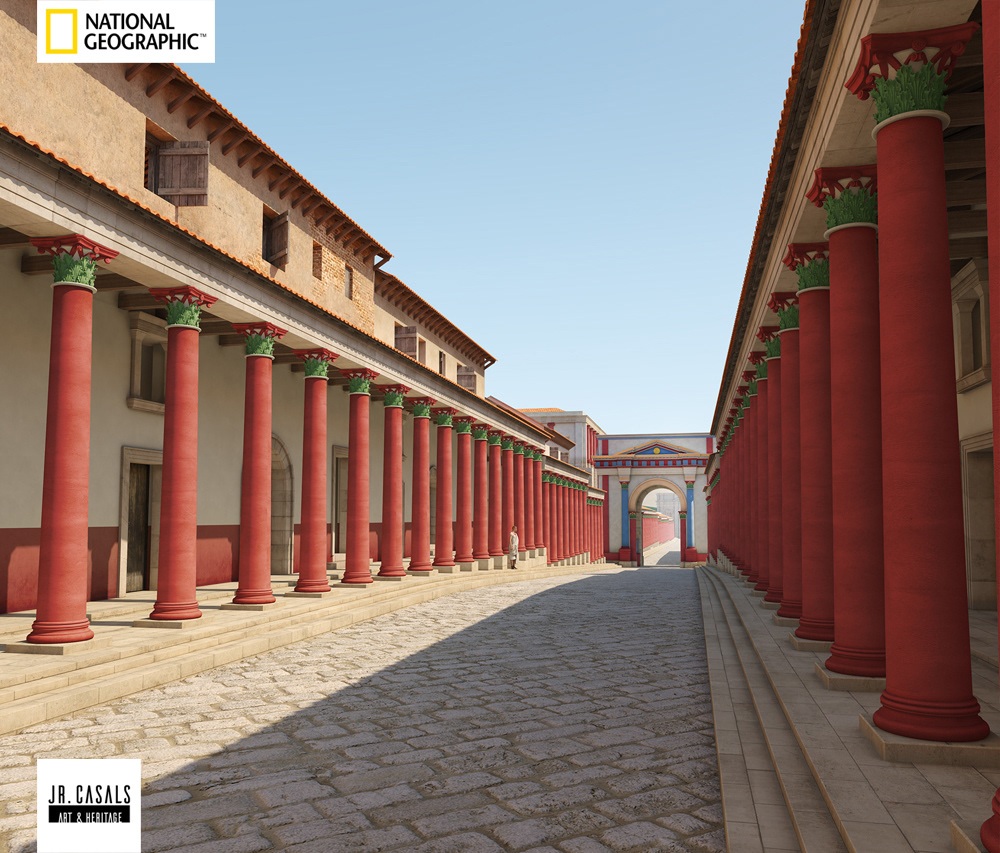

Inscriptions and architectural remains reveal that Gerasa had a vibrant commercial sector with numerous shops lining the colonnaded streets. The market (agora/macellum) would have been bustling from early morning, with vendors selling produce, meats, fish, breads, and imported goods.

Of particular interest is evidence of industrial activities in Gerasa. Excavations have identified areas for metalworking, with the discovery of an “exceptionnel atelier de fabrication de grands bronzes” (exceptional workshop for manufacturing large bronze items). This indicates skilled craftspeople were creating substantial bronze works in the city, perhaps including statuary and architectural elements.

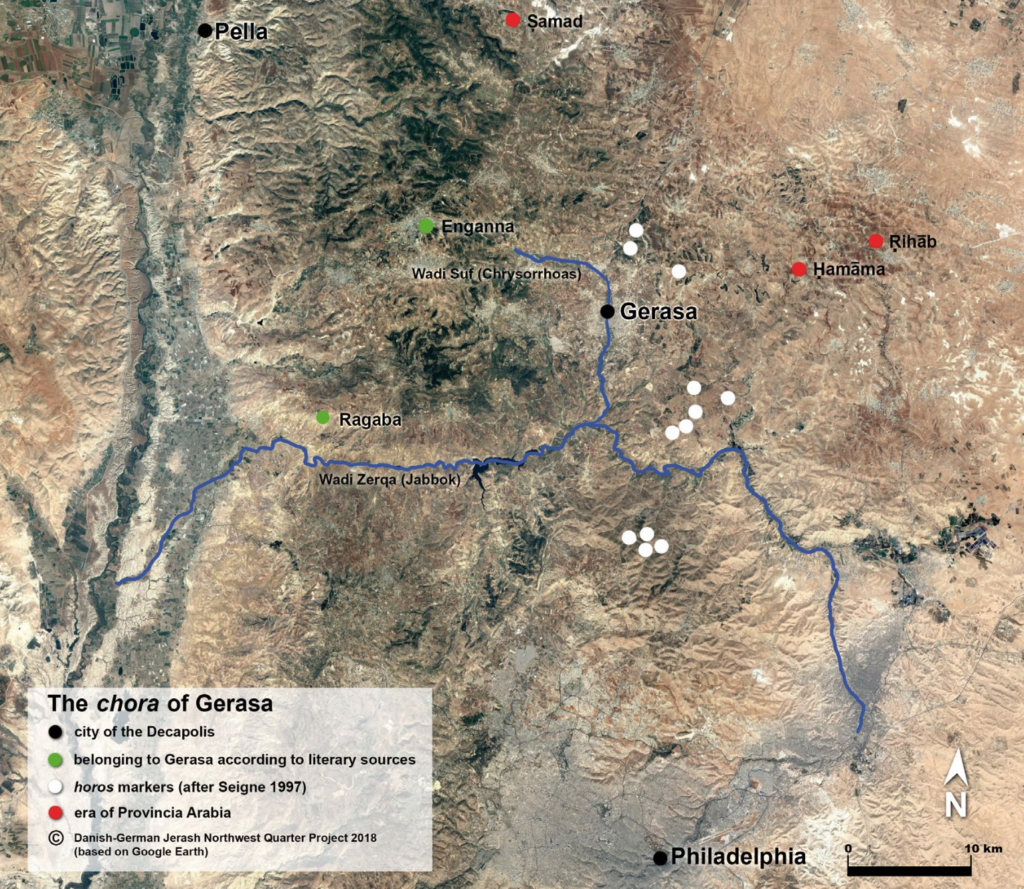

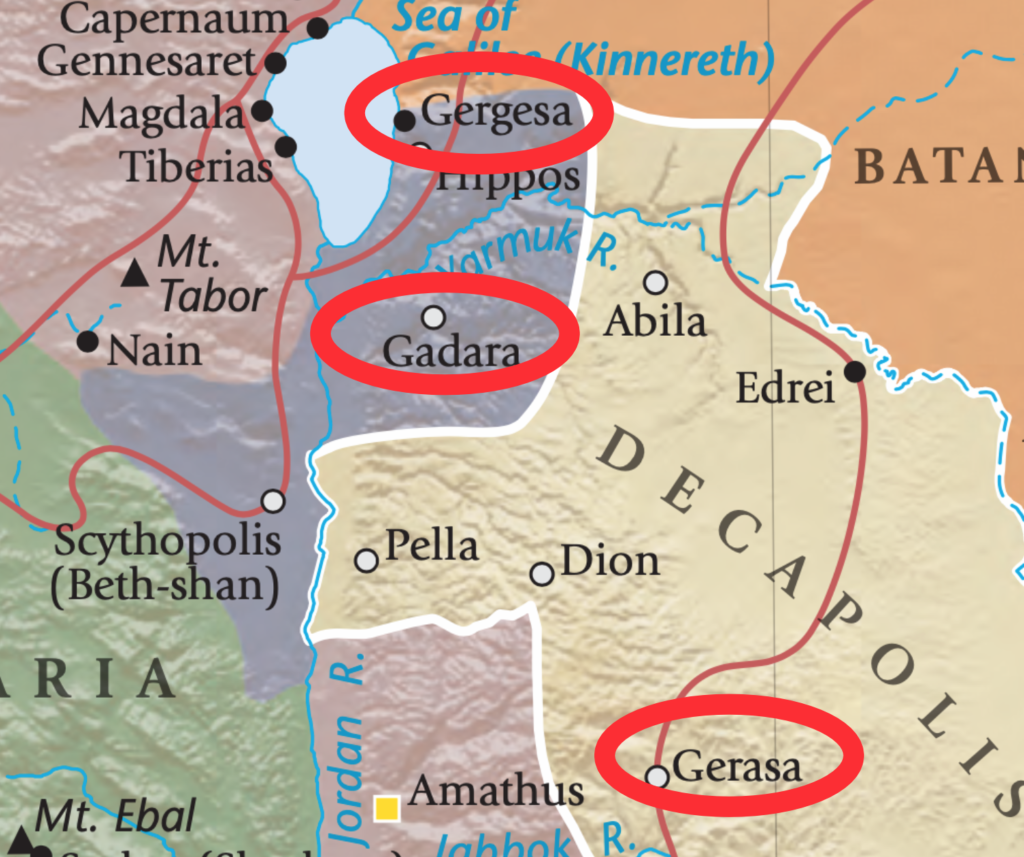

Agricultural labor was fundamental to Gerasa’s economy, with many residents working fields in the surrounding countryside. An inscription referring to the “gardeners of the upper valley” of the Chrysorrhoas (golden river) suggests organized associations of agricultural workers. These gardeners formed a formal association, indicating they were not merely laborers but likely landowners who participated in the city’s socio-political life.

Professional Services

Beyond crafts and agriculture, Gerasa supported numerous other professions. Inscriptions mention various civic officials, including agoranomes (market overseers) and astynomes (responsible for streets and city maintenance). The presence of these officials suggests regulated commercial and urban activities.

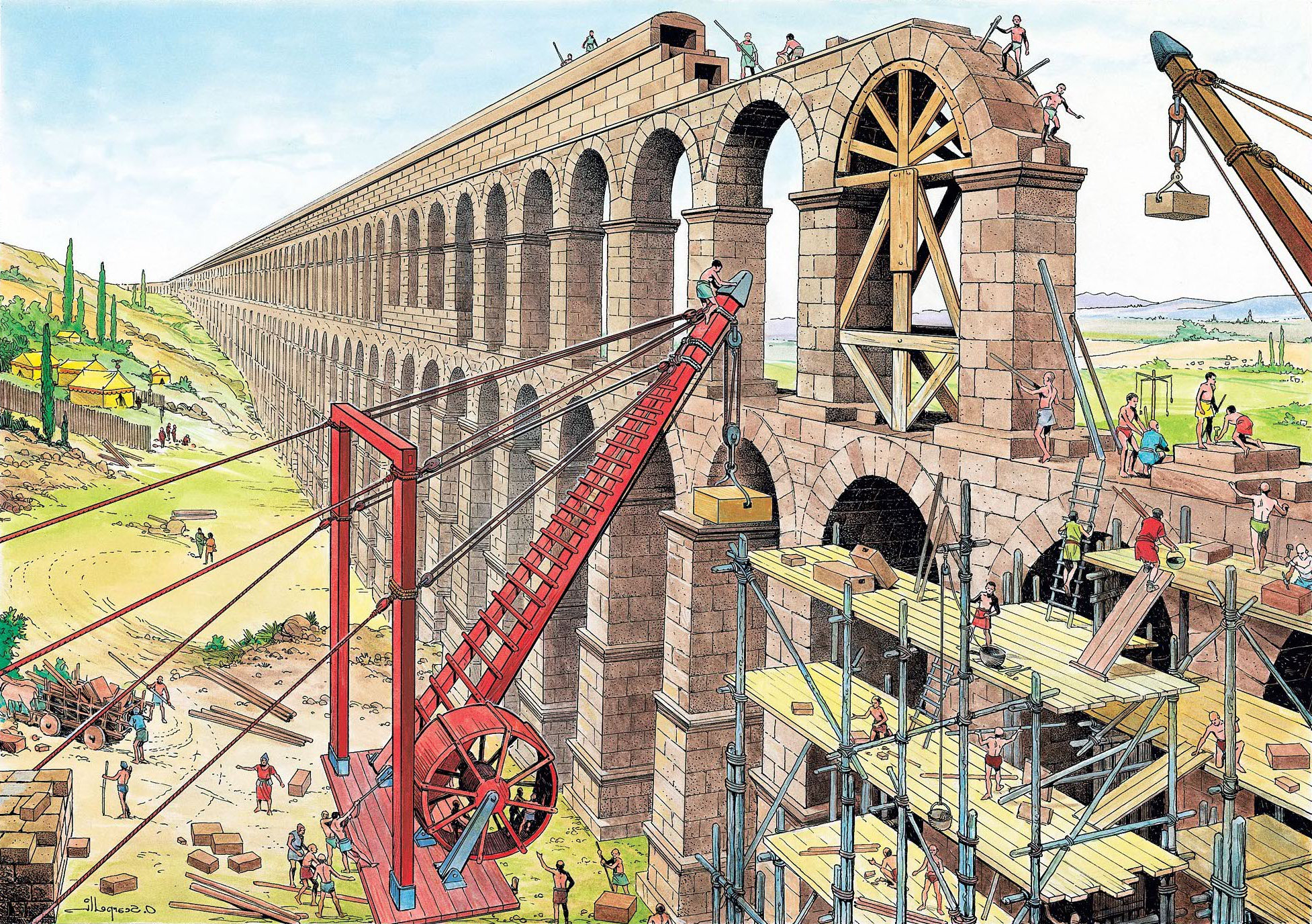

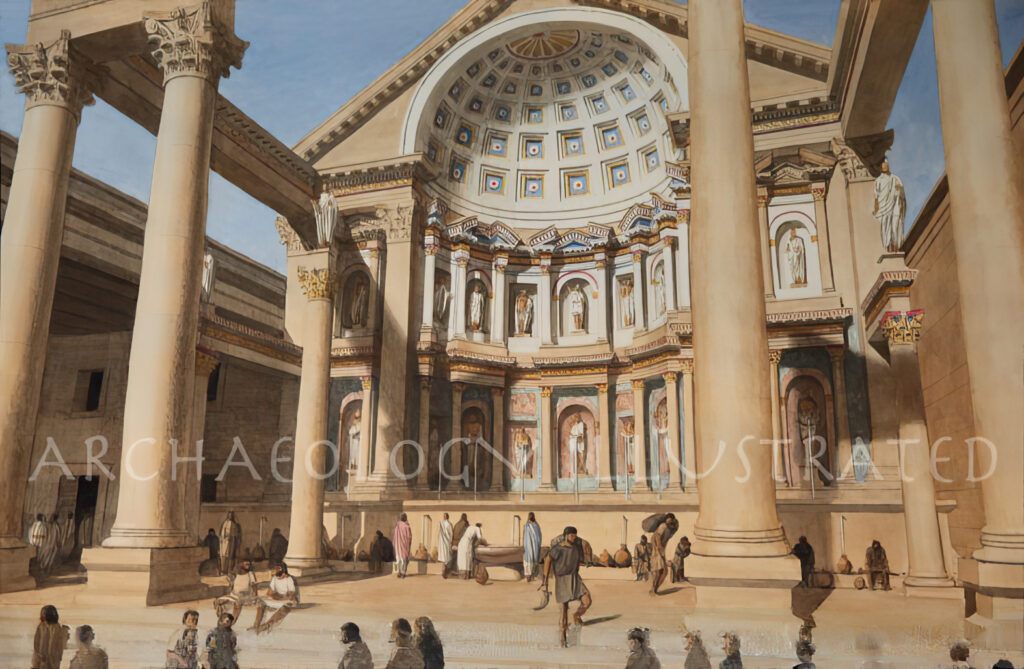

The extensive architectural remains throughout the city attest to active construction trades, employing architects, stonemasons, and laborers. One notable architect, Diodoros, son of Zebedos, is specifically mentioned in inscriptions as the designer of the innovative vaulted corridors and propylaea of the lower court of the Zeus Olympios sanctuary.

-> Explore the political structure that governed these professions in our article “Governance and Administration in Gerasa”

Leisure and Entertainment

Public Spectacles

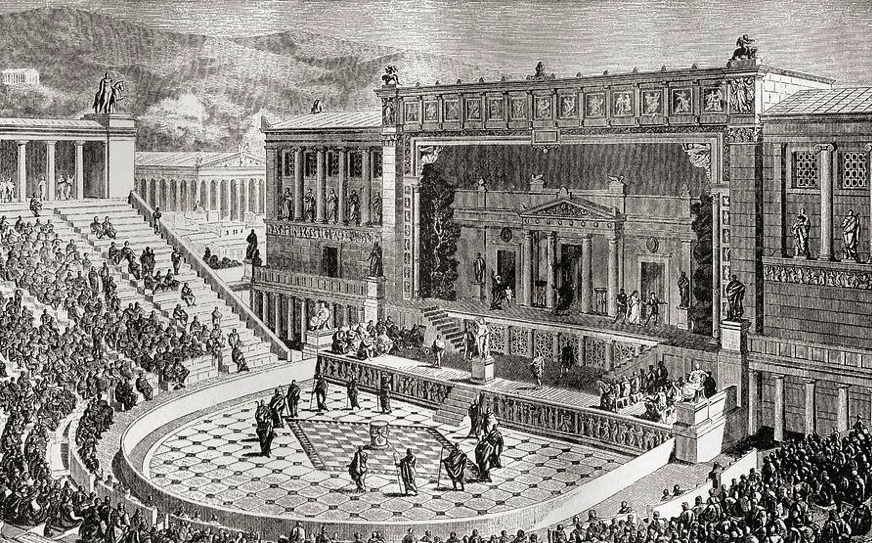

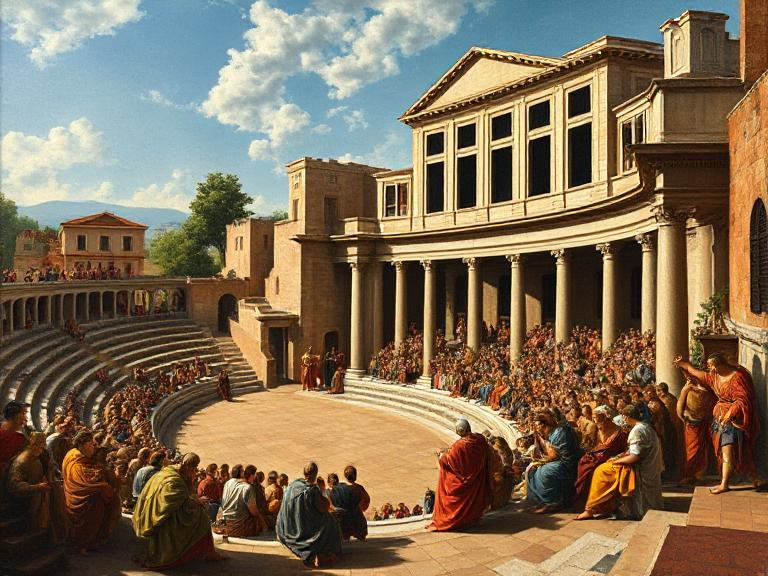

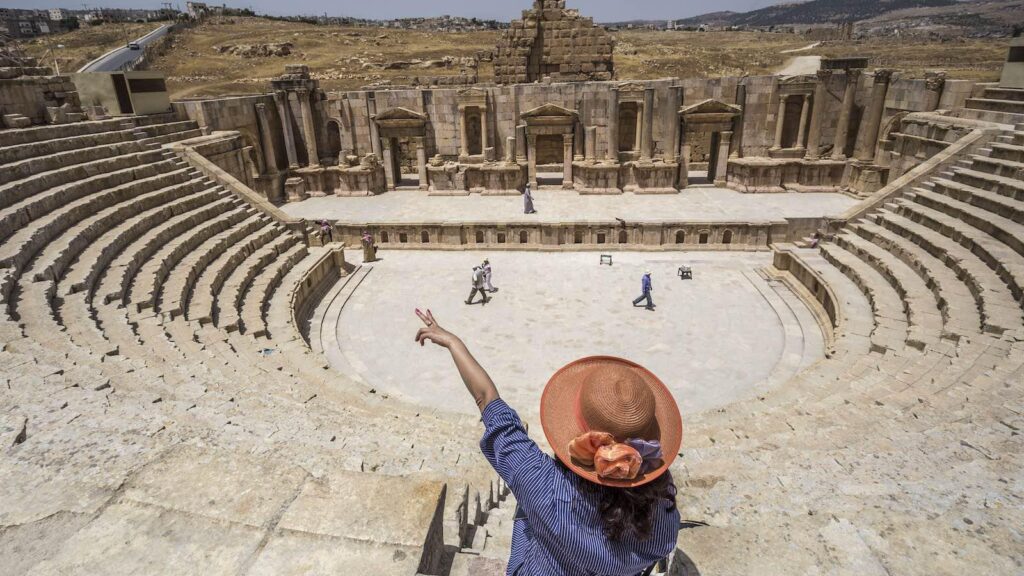

When not working, Gerasenes had various leisure activities available to them. The well-preserved South Theater, with its 32 rows of seats accommodating approximately 3,000 spectators, hosted performances of Greek and Roman dramatic works. The North Theater, though smaller, likely served both as an odeion (covered theater for musical performances) and a bouleuterion (council chamber).

Inscriptions and architectural evidence also suggest that the hippodrome hosted chariot races and other spectacles. These events would have been major social occasions, drawing crowds from throughout the city and surrounding countryside.

Religious Festivals

Religious festivals marked the calendar in Gerasa, providing both spiritual observance and entertainment. The sanctuary of Zeus Olympios and the later Temple of Artemis were centers for major civic celebrations.

Although specific details of Gerasa’s festival calendar are not fully documented, comparative evidence from other cities in the region suggests these would have included processions, sacrifices, feasting, and competitions. The discovery of a courtyard with a fountain near the temple of Zeus, along with an inscription referencing the “miracle of turning water into wine,” indicates some form of public religious festival where this transformation was enacted annually.

Private Pastimes

In private settings, board games were popular pastimes. Though specific gaming pieces from Gerasa are not extensively documented in the available sources, comparative evidence from the wider region suggests games like latrunculi (similar to chess) and dice games were common entertainment.

For the educated elite, literary pursuits were important. The discovery of various Muse statues in Gerasa, including Melpomene (the muse of tragedy) and other identifiable muses, suggests cultural appreciation of poetry, music, and literature. These statues may have decorated a Museion (shrine to the Muses) or another cultural institution in the city.

-> Discover more about religious practices in our upcoming article “Religious Landscape of Gerasa”

Daily Life Across Social Strata

Elite Experiences

The daily life of Gerasa’s elite differed markedly from that of the common people. Wealthy citizens might begin their day with clients visiting their homes seeking patronage and support, following the Roman clientage system. Their days could be filled with civic duties, business oversight, and social engagements.

Archaeological evidence of elite residences in Gerasa is limited in the current excavations, but the quality of imported marble, mosaic floors, and architectural elements suggests considerable private wealth. The donation of public monuments by private citizens, such as “Demetrios, son of Apollonios,” who is recorded as having donated “the construction” to the sanctuary of Zeus as a former priest of Augustus, demonstrates the civic engagement of the wealthy.

Common Experiences

For the majority of Gerasa’s inhabitants, daily life revolved around work, family, and community. Living in simpler dwellings, often apartments or modest houses, they would share communal facilities like fountains for water collection.

Children likely received varying levels of education depending on their social status. While formal schools are not specifically documented in the available evidence from Gerasa, the presence of inscriptions throughout the city suggests literacy among at least the upper and middle strata of society.

Conclusion

The daily life of Gerasa’s inhabitants during the first two centuries AD reveals a vibrant, multicultural community adapting Greco-Roman practices to local conditions. From the food they ate to the clothes they wore, from their working hours to their leisure activities, Gerasenes participated in the broader cultural koine of the Roman East while maintaining distinctive local traditions.

Archaeological evidence continues to expand our understanding of everyday life in this important Decapolis city. Each new excavation, inscription, and artifact adds detail to our picture of a thriving urban center where diverse peoples came together under Roman rule, creating a unique cultural mosaic at this crossroads of civilizations.

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

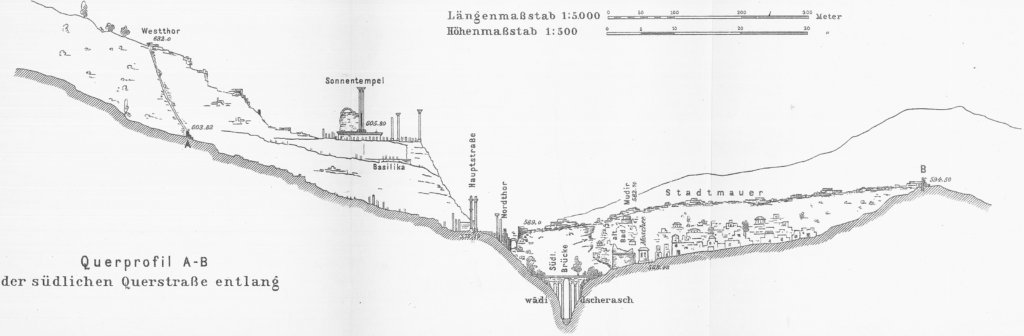

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

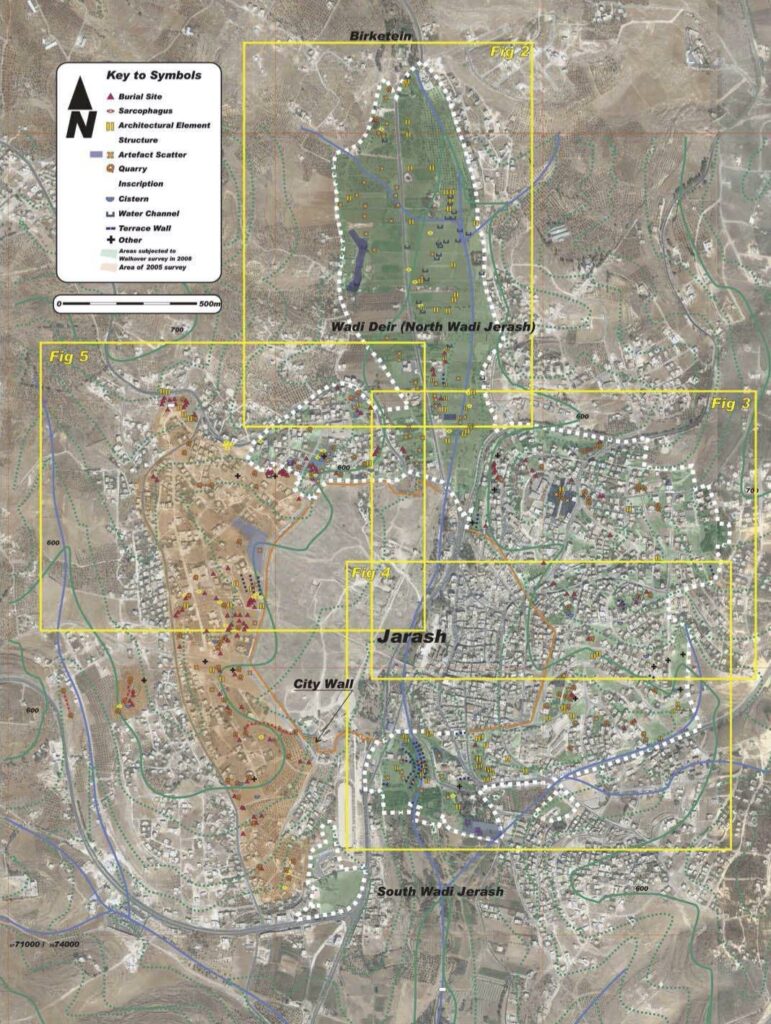

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

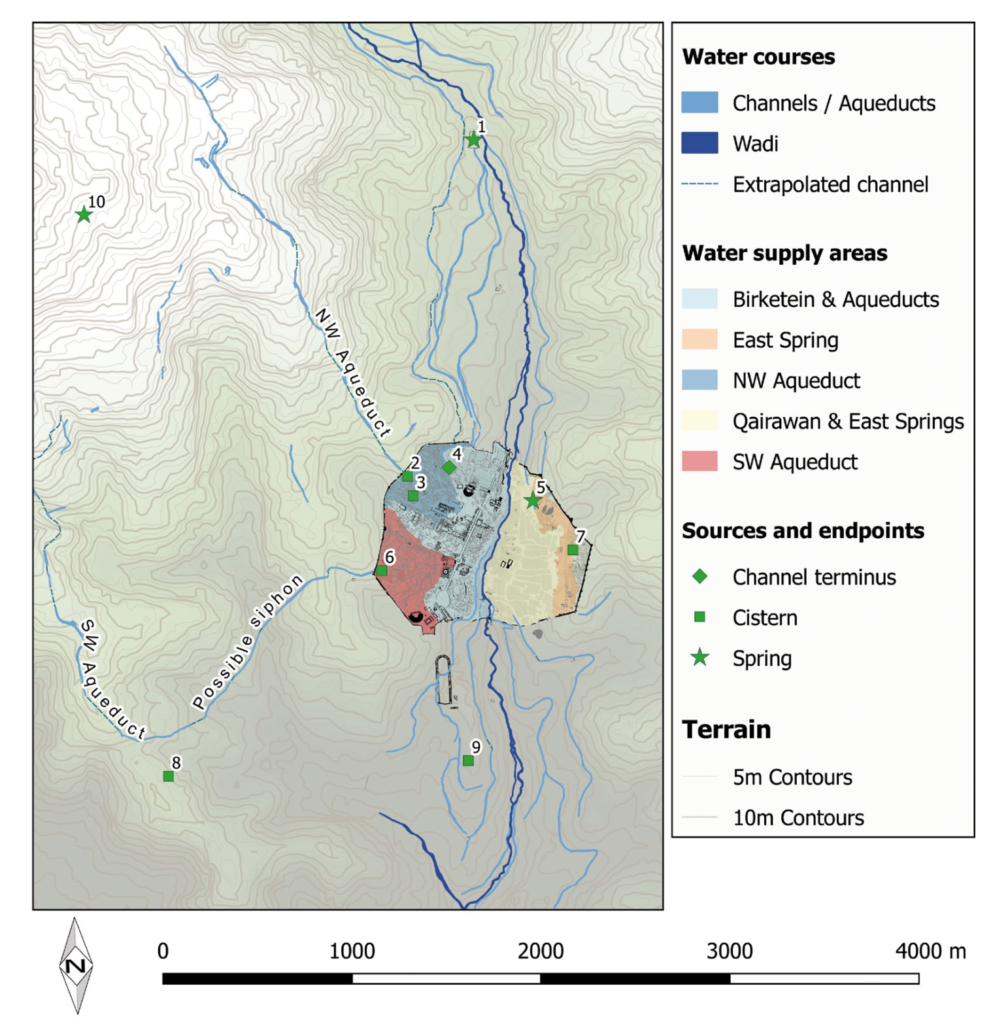

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja